I like new things. I like the gadgets. But minimally. I like well made things. Old things. Old things that were built to last. I tolerate plastic only so far as I must. I prefer the touch of wood, metal, glass, clay, and stone. I may live in a post-modern digital reality, but I like typewriters. I like leather bound journals and fountain pens. I like the old worlds which perennially remain here like olive trees, lest they fall victims of war.

Cast iron pans have been a long favorite, carrying on in the kitchen steps of my grandmothers. Calling it a member of the family doesn’t seem like it does full justice to the nature of the relationship. Corporations of every size refer to their employees as “family,” which is both suspect and appropriate knowing how awful some families can be to one another. A more accurate description would be a baby. A baby is never argued with. Frustrating at times, certainly. But you learn to read a baby, and attend to its needs. Keep me dry. Keep me warm. Hold me. And in return, joy and crows’ feet.

I bought a few cast iron pans like the ones that my grandmothers summoned lifetimes of meals from ovens and stovetops building a seasoning thick and black, never knowing where pan ended and the bacon grease began. Do not use soap. The meal is continuous like the coal of the sprite fire of our native relatives.

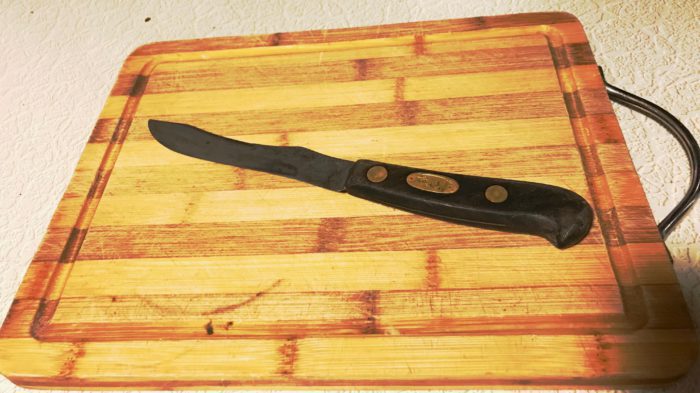

When my final grandmother left the living, and all her life’s many accumulations were turned out to the family, strangers, Goodwill, and the dump, I asked for her letters, her journals which were mostly wall calendars filled in two square inches at a time, her datebook, a cast iron pan, and her butcher’s knife.

The letters and journals were kept by her oldest son as far as I know, as he should. Who knows what happened to her date book. The cast iron pan I took was a small thing. It was new to her in the last decade of her life, when she was rarely serving up crepe-like pancakes, but still might fry an egg from time to time, and having something smaller was much easier to lift. I don’t mind that it wasn’t her lifelong friend. It was the companion she needed during her conclusion years.

But the knife…

I’d seen it in her nimble hands all the years I knew her. That’s no surprise since her country farm house hadn’t changed since her husband died in 1980, and likely not for sometime prior. He was gone by the time my mother married his youngest son. My post-mortum retroactive grandfather had fought in World War II. Even brought home an old artillery shell that was used as a doorstop. He and my grandmother fell in love through letters that he wrote at night and kept him fighting during the day. When he returned from the war, they married. But the knife was brought into the world within a few years of Grandma Z.

Just after Armistice Day concluded the war to end all wars, which ended nothing except thousands of lives, the Robeson Rochester Cutlery Company rolled out their line of Red Pig knives. As the twenties began their roar, someone walked into a department store, and laid a hard saved 50¢ on the counter to treat their family to something fine. Carbon steel. It oxidizes if it gets washed and water sits on it. Keep me clean. Keep me dry. Hold me. And in return, the years are cut through like fresh, salted, sweet-cream butter.

And when her mother, then father, passed away—the red paint that filled the brass relief embedded in the wooden handle long vanished, leaving the pig as a brass in brass—the knife passed into her kitchen. Corn separated from cob. Meat separated from bone. Tomato sliced thin, before resting them on a plate with flowers painted on the edges. White fat cut from cured bacon and spread on country rye.

Sharpened down over a quarter inch over its near century. I sharpened it most recently two years ago, on my way to kill roosters, certain that she’d be pleased that it was still getting farm use, and that I remembered her. I use that Robeson Rochester Cutlery Company Red Pig butchers knife every day with her ghost. Perhaps when it passes to the hands of my niece or nephew, we’ll have a more complete sense of how far 50¢ spent in 1922 can stretch.