A New Introduction

Today is Aunt Madge/Venus’s birthday. As I go further and further into my life as a writer and a poet, I think of her often. She was one of the people who first demonstrated the life of a poet in the world as well as one of the first relatives who took interest and invested belief in me as a young poet. Her influence in my life looms large. She self-published a book of thirty-four incredible poems. I’ll add one at the end of the post. Also, her memorial service was a beautiful mix of family and friends from some of her twelve-step programs. After I read the following introduction and poem for her, I was approached by a woman whom Aunt Madge had been a sponsor to. She told me about how Madge would call her every morning and ask “what are you grateful for?” The woman said she would get frustrated, angry, or upset with Madge’s persistent question, but it was also one of the primary things that saved her life. When I returned home, I conveyed the story to a dear friend, and to this day, all these years later, we write each other an email almost daily, expressing to each other what we are grateful for.

Today I am grateful for the life of Aunt Madge.

Original Introduction

My Aunt Madge is dying. Cancer is eating her body. I am across the country and will be when she finishes her life. The one gift that cancer offers, against the backdrop of so many cruelties, is that it tells you quite plainly that your life is finite; get your life in order. This happens not only to he or she who has the cancer, but to those in their life. This person is going away, what is left undone between you? What words must be shared? What tributes must be given to this one before opportunity passes, and we’ve only stones, wind, water, or a field to speak to?

My Aunt Madge is a poet, an artist, and a spiritual warrior. I wrote this poem to her when I thought there were but hours left for her. She has a little more time than that, but the time is soon. I’ve deliberated on whether or not to post this poem on such a personal matter. I’ve decided to post because I don’t know anyone who’s life cancer has not touched, nor do I know anyone who does not have a “Madge” in their life who is the cavalier spirit who inspires them to struggle with the beauty and bile. This poem is for, and to Madge, but it is for and to all the “Madges,” and the people who love them.

Because this is a personal poem, and is geared for a specific audience of one, there are some inside references that might be helpful to know about as you read. When I reference my own father, I am specifically referencing him and the wounds that come from the Vietnam War. The “ancestral pool” is the pool that stood in the backyard at my grandparents’ home. My grandfather—Madge’s father—was an alcoholic and an inventor of sorts. He had an aptitude for understanding how things worked and could envision how to create something to solve the problem at hand. This is what he did with the pool. I was very young when it stood, and he would labor at keeping it running. While I might be cobbling together a few different memories, I do believe that the pool filter had parts of an old vacuum cleaner that played some vital role in the filtration system. In his time of dying, my grandmother said that there were only two times that she’d ever seen him cry during the length of their entire marriage. The first was when baby Sara died, an aunt who only breathed life as an infant. When Madge was born, there was some complication, and she had to be operated on. Back then, and perhaps now, babies were not anesthetized. This was the second and last time my grandmother saw my grandfather cry.

I talked to Madge about that once, and what she said stilled me. I thought of the scene as one where there was real evidence of love coming from a man (being a man of his times) who had very few means to express love. What she said was that for those very same reasons, it was an enormous burden to know that her life (which was hanging in the balance) invoked such a sense of helplessness, unable to fix with any level of ingenuity, labor, or prayer, that he who in seventy-odd years cried but twice, was one of them. It is for this reason that I’ve written about only our fathers and not our mothers, who certainly had their hand in stirring the soup of our lives. The pool (did you forget that this is an explanation of a pool?) was, therefore, a very real pool, but also carries all the spiritual weight of our lineage, and the effort to create relief for the people that we love, be it from heat of a Michigan summer or the strains that a life can carry.

The seahorse mentioned is a tattoo that Madge has high on her leg, which could only visible to our family when she wore a swimsuit. What the seahorse meant to her, I suspect I’ll never know.

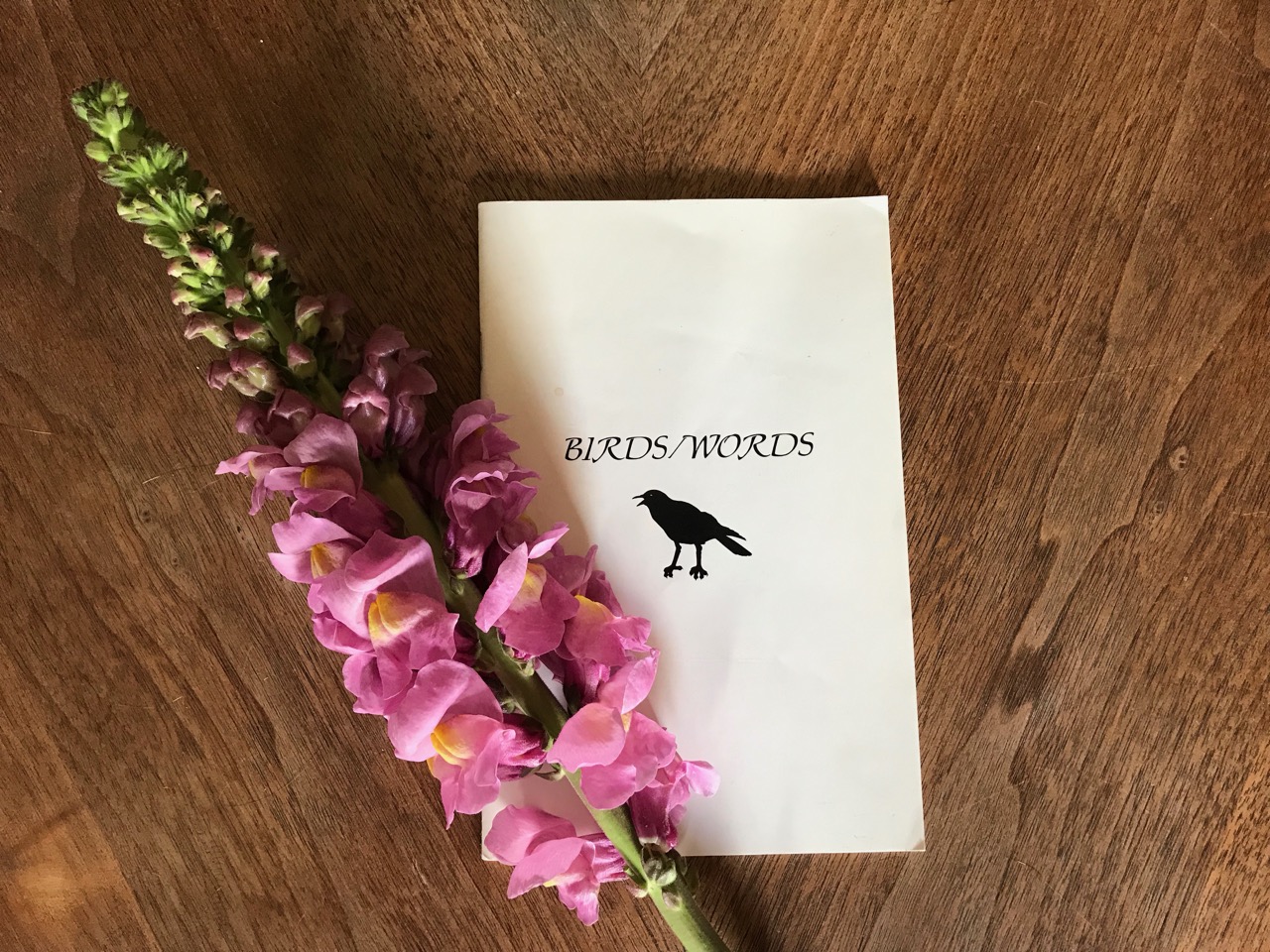

A few years ago, Madge decided that she would bind and print a book of her poems. Just a short print, nothing for stores or making her big break, but something to put in the hands of the people of her life. The name of the book is Birds/Words.

There are two quotes cited, the one that repeats is from a poem that Madge shared with me once, and the other grabbed me once upon a time when reading “Mutant Message Down Under” by Marlo Morgan. The phrase captured is one that the Aborigines say to every baby born, and everyone who dies.” Since reading it, I’ve whispered it to every newborn I encounter, and every loved one who dies. It would be a great wish of mine to have someone say it to me when it is my time to depart. I am saddened that I have to say it to Madge from such a distance, and through poetry rather than in person.

Aunt Venus

There is one last chance to speak to you

Poet to Poet—

Which is to say—spiritually,

Unencumbered by formal contrivances,

Or common truisms, which are true-ish at best,

And that resounding gong, so often mentioned at church weddings

Bring more nausea than comfort.

Be silent resonant metal, there is truth to speak softly.

Aunt Venus,

You do not hide what is woman under windblown crimson hair,

While standing coy on the bottom lip of some clam or mussel,

Nor have interest in the lives of nymphs, or otherwise.

So where did this name arise from in the mind of a boy,

With no knowledge of myths, or high art?

Was it perhaps a transmission of a truth in DNA?

My father loved you, not as lovers,

but as two warriors,

whose truth of pain could not be carried

into plain conversation,

which took comfort in being understood.

Your seahorse, which swam in the ancestral pool—

one built of ingenuity and held together with gin and crusted elbow grease—

was my first example of a tattoo—the easiest understanding of beauty through suffering.

Some suffering self-inflicted,

Some suffering inflicted by malice, neglect, and coincidence.

All life.

And the second part of the lesson you shared

In quotes

“It is never the opposite of love.”

Those words, cleverly shared

Are now one mantra,

tattooed inside me.

As farewell is upon us,

May all the wounds dissipate,

May your sword, and shield, and pen, and brush,

and all the old tools of life

rusted and well used,

pass from your hands with ease.

While death comes,

and you explore a new mystery,

be it life ever after,

or life completed,

Be at peace,

as my father,

and yours,

be in love as all the cherry blossoms on my part of Earth,

be in joy, as the laughter of grandchildren,

and be renewed as breath shared,

like one reading the poetry of another,

tingling with the electricity of one’s life, their birds, and words passing through another.

With love, respect, and peace,

With gratitude,

and with words borrowed again

“We love you and support you on the journey”

and none of this, however awesome or terrible,

“is ever the opposite of love.”

A poem from Aunt Madge’s Book

MY FAVORITE

by Madeline Weaver

When I

first

bite

into a pear,

the taste

is one of

human sex.

Now how do you think

she

worked that out?

That shape you see…

Oh man! Hold it in your

hand…

is for

an

orifice, a palate,

dusted

with

primitive!